CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

West Road, Cambridge CB3 9DR. Tel: (01223) 333000 (Enquiries)Fax: (01223) 333160 E-mail: library@ula.cam.ac.uk

This exhibition is part of the nationwide commemoration of the 400th anniversary of Cromwell's birth.

Introduction

Case 1. The countryman

Case 2. Member for Huntingdon and Cambridge

Cases 3 & 4. The cavalry officer

Case 5. The reluctant radical

Case 6. The regicide

Case 7. The Commonwealth General

Case 8. Cromwell and Cambridge

Case 9. The Lord Protector

Case 10. Emperor of Britain

Case 11. A brave, bad legacy

Images of some items featured in the exhibition

Cromwell was born in Huntingdon on 25 April 1599. Following the traumatic upheavals of civil war and regicide, he rose from the ranks of the minor gentry to become Lord Protector and ruler of England, Scotland and Ireland, enjoying the powers - if not the title - of king. Buried with royal ceremonial in Westminster Abbey, his corpse was dug up and hanged on a gallows less than three years later. From that day to this, the controversy surrounding his extraordinary career has divided professional historians and the general public alike. Some see Cromwell as the defender of principles and liberties, the champion of religious diversity and toleration, while for others he was nothing more than a tyrant, a murderer and a bigot.

This exhibition tells the whole dramatic story, drawing upon treasures held in Cambridge University Library, the Fitzwilliam Museum and Sidney Sussex College,where Cromwell studied for a year. While covering every aspect of his life - the cavalry captain, the army general, the Member of Parliament and the statesman contemplating wide horizons - the displays also seize a welcome opportunity to fix Cromwell in his local context, the farmer from Huntingdonshire who was offered, and refused, the crown itself.

Return to contentsFor forty years Cromwell lived on the cusp of the haves and the have-nots. His father was the younger son of a knight, and so Oliver inherited only scraps of property, barely enough to sustain gentle status. Business failure caused him to sell up in 1630 and move to St Ives as a working (yeoman) farmer. The death of his mother's brother childless in 1637 restored a modest prosperity - he inherited leases from the dean and chapter of Ely - and gave him a substantial house near the Cathedral.

On the other hand, his grandfather - living in a great house just a

mile from Huntingdon, a house he must have frequently visited - often

entertained kings and courtiers, and Cromwell's in-laws (he married

Elizabeth, daughter of Sir James Bourchier in 1620) brought him into

contact with wealthy London merchants and great puritan peers

interested in colonial development, especially the Earl of Warwick. A

puritan "conversion" experience, linked to a mental

breakdown in 1630, changed his life; and throughout the 1630s he was a

man waiting for God to give him a job to do:

"if here I may

serve my God by suffering or by doing, I shall be most glad".

Cromwell was MP for Huntingdon in the Parliament of 1628-9, and for Cambridge in the Long Parliament elected in 1640. On both occasions he probably owed his election to aristocratic patronage; and on both occasions he was quite probably the poorest man in the House of Commons. He was well nigh silent in 1628-9, but from the beginning of the Long Parliament he was a firebrand, taking up extreme positions - he was an outspoken critic of the Bishops and one of the first to call for the established church to be pulled up "roots and branches". He further proposed the introduction of annual parliaments, insisting that Parliament and not the King should appoint army generals. He seems to have been used by aristocratic leaders to test the waters, to see how far they could push.

After fighting broke out in 1642 Cromwell spent all but five of the forty-five months of war in the field, but his appearances in Parliament provoked some of the greatest crises - as in the winter of 1644-5 when he excoriated many of the Generals - especially his own commanding officer, Edward, 2nd Earl of Manchester, for preferring to pursue a negotiated settlement with the King to outright military victory and an imposed settlement.

Return to contentsIn September 1642 Cromwell was commissioned as a captain of horse. By the spring of 1643 he was a colonel of horse and by the autumn he was Lieutenant General of Horse in the army of the Eastern Association: Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Cambs, Hunts, Herts (and later Lincs). In April 1645, the three major Parliamentarian armies were amalgamated, but all officer-MPs were expected to stand down to concentrate on their duties at Westminster. Because the Houses could not agree who should command the cavalry, Cromwell was appointed on a whole series of temporary (forty day) contracts; and he only secured a long-term commission in 1647.

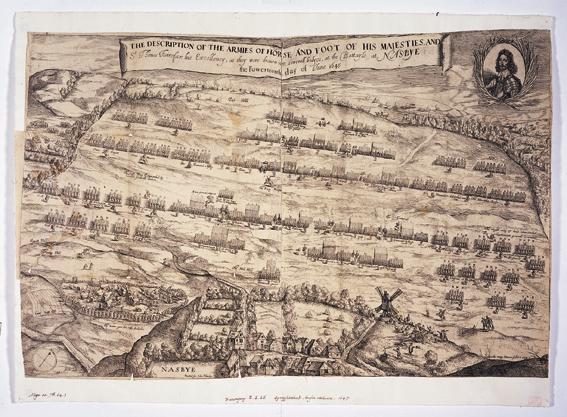

Between 1643 and 1646, he fought in numerous battles across England, leading charges critical to victory at the two greatest of all civil-war battles at Marston Moor (outside York) in July 1644 and Naseby (south of Leicester) in June 1645.

He sought only to recruit "honest, godly men ... a plain russet-coated captain that loves what he fights for and loves what he knows". He fiercely defended such men when they were accused of excess zeal (for example, requisitioning goods from "delinquents", or cavaliers) and he protested against the religious intolerance of the Scots and their Presbyterian allies who were determined to replace a narrow Anglican conformity with an equally narrow and specific form of puritan conformity.

Return to contentsParliament won the all-out victory Cromwell had worked for; but Charles I refused to admit defeat or to negotiate seriously. Instead he exploited divisions amongst his enemies and played them off against one another. In the summer of 1647, Cromwell and his senior army colleagues decided to negotiate directly with him themselves. They were duped in turn. Radical voices began to call for the King's execution and for the whole system of government to be dismantled and replaced by something rooted in the consent of all free people (by an Agreement of the People or new social contract) which limited the authority of all those elected to serve.

Cromwell was not "wedded and glued to forms of government" and he believed that all such forms were "dross and dung in comparison of Christ". For him, this meant that one did not rush to change forms for the sake of it. Any government which guaranteed fundamental civil rights and which guaranteed freedom of belief and practice to all sincere Christians was acceptable to him. And he persevered until late 1648 in believing that these good ends of government could be achieved by massaging the existing institutions. He therefore fell out with political radicals such as the Levellers while retaining the support of most religious radicals.

Return to contentsIn late 1647 Charles I engineered a new civil war in which he was encouraged by many of his old supporters, many disillusioned Parliamentarians, popular agitation against high taxes and the collapse of law and order, and a promised Scottish invasion. Cromwell and most of the army saw this as an act of sacrilege, an attempt to overturn the judgement of God in the first war and they determined to punish those responsible for the shedding of innocent blood. Cromwell led an army to put down rebellion in South Wales, then intercepted and crushed the Scottish army at the battle of Preston and harried the remnant back into central Scotland.

Having triggered a coup in Edinburgh to restore men he thought he could trust to co-operate with him, he moved back to England to mop up royalist resistance in Pontefract and other towns in the West Riding. He himself probably held out longer than most for a trial, followed by the King's deposition (not execution) and the accession of one of Charles' teenage sons. Only when the King refused to abdicate as a way of preserving his dynasty did Cromwell agree to regicide. But once set on the trial and execution he was ruthless in seeing it through and in rallying waverers.

Return to contentsThe English people were too stunned and weary, too cowed to rise up against the establishment of the Commonwealth. But the Scots and Irish overwhelmingly proclaimed their intention to assist Charles II to secure all his thrones. Cromwell was sent first to conquer Ireland and then Scotland. He began (but did not complete) the conquest and subsequent incorporation of both into an enlarged English state. He spent nine months in Ireland and fifteen months in Scotland. With his defeat of a Scottish Army commanded by Charles II in person at Worcester, on 3 September 1651, his own fighting days were over.

Throughout this period, and especially after his return from Worcester, he was also a glowering presence in politics, first in the "Rump" of the Long Parliament, which had become a single-chamber body concentrating in itself all legislative and executive authority. He opposed the Rump's (highly successful) war against the Dutch and lobbied for Parliament to develop strategies for long-term constitutional settlement, for social justice and more equitable due process at law, and for a programme of Christian evangelism alongside a broad religious toleration.

Already his name was linked to supreme power. A German ambassador heard a counsellor of state say, as they watched Cromwell's return in triumph from Worcester, that the Lord General was "unus instar omnium et in effectu rex" : he is a man set above all others, and to all intents and purposes our king.

Return to contentsCromwell enrolled at Sidney Sussex College two days before his seventeenth birthday in 1616. Like many gentry pensioners and a majority of those who matriculated, he came not for a degree but for a veneer of polite learning; however his departure after one year (two was more normal) was probably the result of his father's death. Thereafter his links with Cambridge appear to have been limited until he was elected to represent the town in 1640, possibly as a well-known local puritan, more likely as a man with connections to the Earl of Warwick and his brother, the Earl of Holland - Chancellor of the University. In the high summer of 1642, Cromwell gathered a volunteer force and prevented the movement of a convoy planning to take silver plate from the colleges to swell the King's war-chest at York. It was at once an act of high political calculation and highway robbery, and press coverage made him a household name across England for the first time.

In the mid 1640s Commissioners appointed by the Earl of Manchester removed about half of all the heads of colleges and Fellows, and in a separate purge, ordered the destruction of most of all "monuments of idolatry and superstition" from college chapels and town churches. Cromwell was a regular visitor to Cambridge in the war years (the committee of the Eastern Association had its headquarters in the Bear inn, next to Sidney Sussex College) but he played little personal part in either of these purges. Even after the war, he took less interest in Cambridge than in Oxford, of which he was Chancellor from 1651 to 1657. Throughout the 1650s he permitted and encouraged religious speculation and diversity at the Universities, and condoned quiet, but not open, political dissent.

Return to contentsIn April 1653, Cromwell tired of what he saw as the prevarication, lack of vision and lack of "vim" in the cluster of MPs who had clung on to power as the Rump Parliament since 1649. They were crudely ejected by armed force. Cromwell briefly tried to persuade 140 religious zealots representing "the various forms of godliness in this nation" to design a blueprint for a godly commonwealth, but their internal feuding led to the collapse of this experiment. He then (probably with real reluctance) agreed to be head of a powerful executive council as defined by a new paper constitution. For the remaining five years of his life he served as Lord Protector, refusing all efforts to make him King.

There was a strong authoritarian side to him - government was, he said, for the people's good, not what pleases them; political enemies were imprisoned without trial, and taxes were raised without parliamentary consent. "If nothing were done but is according to law", he told Parliament in 1656, "the throat of this nation might be cut while we send for some to make a law". But he continued working to create a wide measure of religious freedom, and to inculcate respect for God and the moral law by "a reformation of manners, an internalised self-discipline in a people governed not by the interests of the flesh but those of the spirit, a government at last fitted for civil freedom, a government rooted in informed consent.

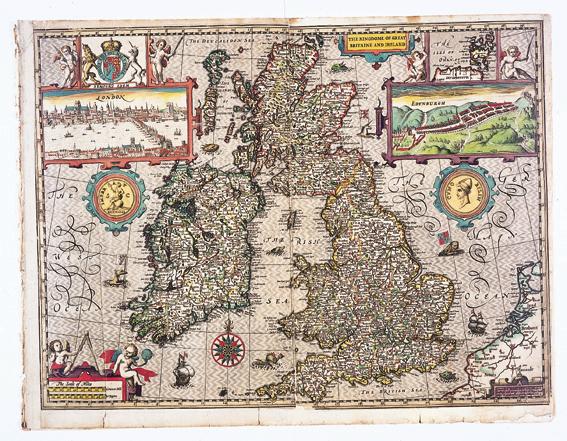

Return to contentsFor the only time before 1801, Cromwell presided over a constitutionally and institutionally united Britain and Ireland, with a single Parliament, a single Council of State and a commitment to the achievement of a single code of law and judicial practice. It was an achievement forged in blood. In conquering Ireland, Cromwell had stormed Drogheda and Wexford and denied quarter to the garrisons of both, killing many civilians in the process. In doing so, he entered into and escalated a sickening cycle of inter-communal violence stretching back for decades. In all he captured 28 towns and castles on and near the east coast but he left the rest of Ireland and the redistribution of 40 per cent of the land mass of Ireland to his successors. The assault on Scotland was less bloody, but not much less bloody.

Once he was Lord Protector, Cromwell made an offensive alliance with France against Spain. He failed in an attempt to wrest Hispaniola (Cuba) from Spain, but he did capture Jamaica; and an English expeditionary army on the European continent won a great victory over the Spanish in the Battle of the Dunes (February 1658) and occupied Dunkirk. He acted to broker a peace between the Protestant Kings of Sweden and Denmark and raised British prestige across Europe to the highest point it was to reach between Agincourt (1415) and Waterloo (1815).

Return to contentsCromwell died on 3 September 1658, the anniversary of two of his greatest victories; twenty months later Charles II was recalled from exile and the monarchy restored. Cromwell had been buried in Westminster Abbey, but in 1661 he was exhumed and hanged in his shroud at Tyburn. His head was cut off and displayed outside Westminster Hall until it was rescued by a well-wisher nearly twenty years later. His reputation took nearly two centuries to recover, and over the past 150 years he has remained the most contentious figure in British history. From the 1840s, his radical Christian paternalism and his commitment to freedom for "the poorest Christian, the most mistaken Christian" canonised him as a hero of many political reformers and religious dissenters; while his fierce (fanatical?) Calvinism and his gloating massacres in Ireland demonised him in the memory of others. Thomas Carlyle's edition of his letters and speeches was one of the ten best-selling books of Victorian England, but attempts to raise a statue to him outside the Palace of Westminster in 1898 led to bitter debates in both Houses and thunderous leaders in the newspapers.

Return to contents

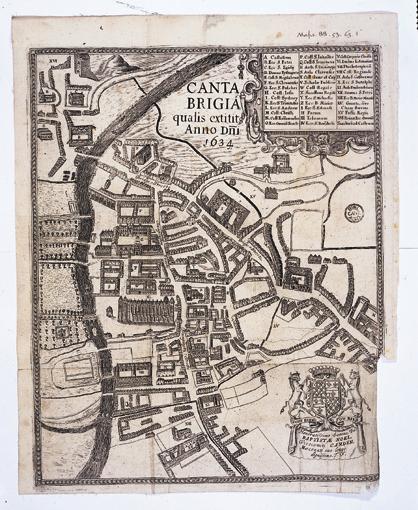

An attractive, if not altogether accurate, depiction of Cambridge in 1634.

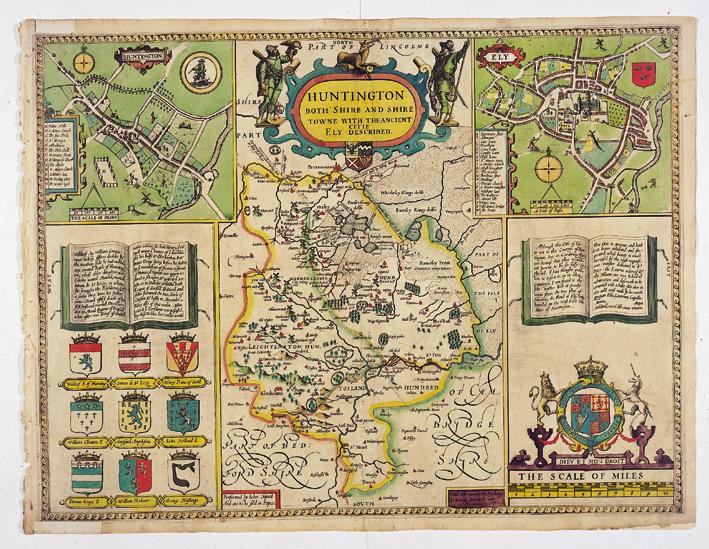

For most of his first thirty years, Cromwell lived in Huntingdon. Thereafter, he resided for seven years in a small farmhouse close to St Ives. This map of Huntingdonshire is from the so-called "Gardner copy" of John Speed's Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain, a collection of sixty-six proof impressions of the maps, c. 1611. Of three known sets of proof, this is the most complete; it is also the only coloured set. Speed's maps were used by both sides in the Civil War.

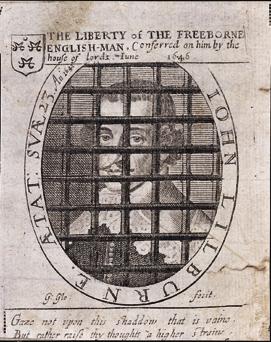

John Lilburne had a long record of principled opposition to the established church. Cromwell helped secure his release from prison in 1640, and Lilburne subsequently served in his regiment from 1643 to 1645. By the end of the First Civil War Lilburne had emerged as one of the leading Levellers, a group of pamphleteers and polemicists who developed views on religious toleration to incorporate far-reaching social and religious reforms, including the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of universal male suffrage. These ideas proved popular among the Army rank and file. Cromwell initially tried to work with Lilburne on constitutional reform, but then turned decisively against the Levellers. He was torn between fears of social unrest and his conviction that particular forms of government mattered less than the principle of godly rule.

The battlefield of Naseby, 14 June 1645, in a contemporary print. A closely-fought battle was decided by Cromwell's cavalry tactics, sweeping away the enemy horse on one flank and then descending on the royalist rear. In effect, this battle decided the war. After Naseby, King Charles's remaining supporters retreated to Oxford, and into Wales and the West Country.

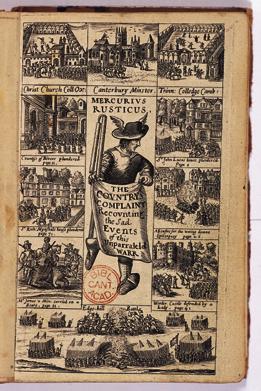

A catalogue of enormities charged against the forces of Parliament,

set out in this royalist work from the last year of the First Civil

War. Its author, Bruno Ryves, was a clergyman from Essex who

specialised in anti-puritan propaganda. The purging of the two

Universities and the desecration of Canterbury Cathedral take

iconographical pride of place.

Charles II's dramatic escape after the Battle of Worcester, donning disguises and hiding in oak trees, could not obscure the fact that the royalist cause had been decisively broken. For Cromwell, who had masterminded the pursuit and destruction of Charles's Scottish army, the battle was nothing less than a "crowning mercy". Fought and won on 3 September 1651, the anniversary of Dunbar, it amounted to one further, conclusive manifestation of God's favour.

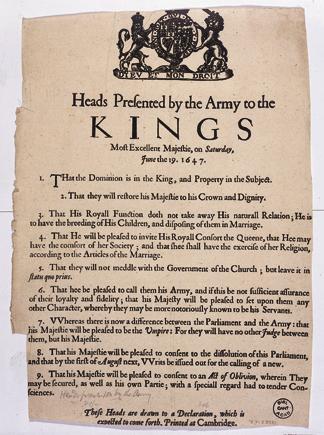

Though victorious in the Civil War, Parliament faced an equally formidable struggle in its bid to secure a workable peace settlement. It strove to disband its various armies - all owed substantial arrears of pay - and relations with the military commanders deteriorated. In June a junior officer, George Joyce, seized the king and brought him to Newmarket. Soon afterwards, the new Army General Council began negotiating with Charles. Their offer was set out in the so-called Heads of the proposals, remarkably generous, and aiming to reduce the powers of Presbyterians in Parliament as much as those of the king. An early draft printed at Cambridge is displayed. Cromwell played a leading role in shaping the proposals, and in the face-to-face negotiations with Charles. Characteristically, however, the king quibbled, while opening negotiations with the Scots.

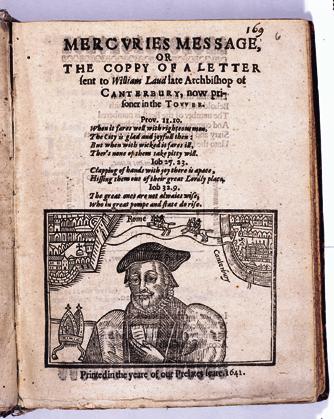

King Charles's religious reforms were spearheaded by William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633. Laud's theology is difficult to pin down, but his aggressive defence of divine-right episcopacy, his denunciation of Calvinist doctrines of predestination, and his refusal to reject outright the teachings of the Church of Rome all helped damn him in the eyes of the mainstream Calvinist majority within the Church of England. The Long Parliament moved swiftly against Laud, impeaching him in December 1640 and committing him to the Tower of London. He was eventually executed in January 1645.

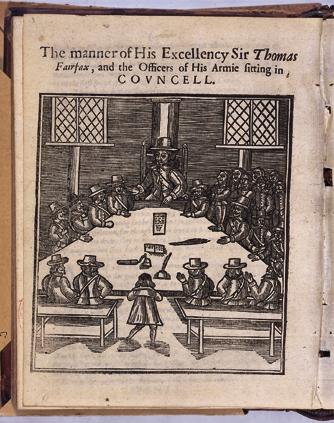

Commander-in-Chief of the parliamentary New Model Army from 1645, Sir Thomas Fairfax presided over the new Army General Council on its formation in 1647. The Army thereafter played an increasingly prominent part in English political life. Despite grave misgivings over the execution of Charles I - he declined to sit in judgement on his king - Fairfax retained his command until 1650, when he resigned rather than lead an invasion of Scotland. Cromwell, his deputy since 1645 and fresh from the controversial conquest of Ireland, was his successor.

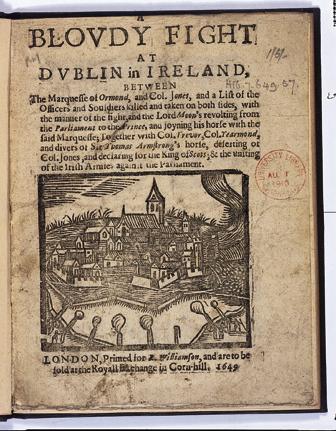

Fears that a royalist Irish army was about to descend on England led Parliament to appoint Cromwell Lord Lieutenant in Ireland on 22 June 1649. Within a month he had landed near Dublin, at the head of a formidable army. Through the following autumn and winter Ireland was "pacified" in uncompromising fashion. The slaughter of soldiers and civilians at Drogheda was followed a month later by another bloodbath after the storming of Wexford. In the face of a ruthless enemy, royalist resistance collapsed and Cromwell left Ireland in May 1650, summoned home to prepare for war against Scotland.

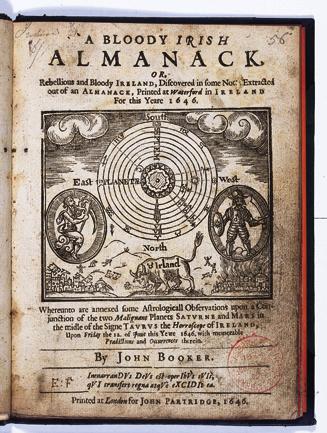

A bloody Irish almanack, or, Rebellious and bloody Ireland ... London, 1646; Hib.7.646.1 |

A bloudy fight at Dublin ... London, 1649. Hib.7.649.57 London, 1650. Hib.7.650.8 |

Cromwell landed in Ireland determined both to pacify the kingdom and to exact revenge for atrocities committed by Catholics against Protestants eight years before. Civil war in England had been mirrored by almost continuous unrest in Ireland, as these works published in 1646 and 1649 illustrate only too vividly.

A fine specimen of the Great Seal of the Protectorate in Ireland, attached to letters patent of the Lord Protector granting lands formerly in possession of an Irish Catholic to the daughters of Colonel Robert Hamond, 1657.

Thomas Manley's translation of a Latin "Gratulatory ode of peace", saluting Cromwell's many military achievements. The result is a series of rather uninspired rhyming couplets. One eighteenth-century reader has scribbled at the end "A very dull piece of poetry". The poem is dated "in the year of our redemption 1652, and of England's restored liberty, 4".

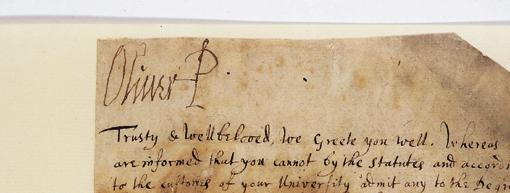

Many University documents relating to the Civil War and Commonwealth were destroyed at the Restoration; however, a few survived. Here is Cromwell's mandate to admit Benjamin Rogers to the degree of Bachelor of Music, signed in the last summer of the Lord Protector's life. His signature is that adopted after 1657, the quasi-regal "Oliver P[rotector]".

The new republican administration in London believed that England's security depended on the rapid and thorough suppression of royalist forces in Ireland and Scotland.

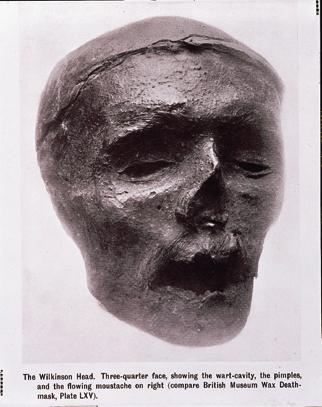

The head of Oliver Cromwell, now at Sidney Sussex College.

Return to contents