| |

|

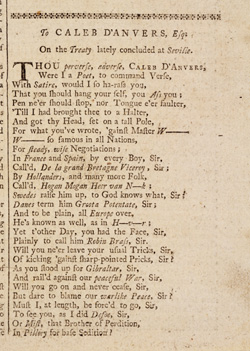

| Part of a poem from The craftsman, No.

185, January 1730. ‘W–––’ is Robert

Walpole, ‘N–––k’ is Norfolk, his home

county, and H––v––r is Hanover. Daniel Defoe

and Nathaniel Mist both stood in the pillory after convictions for

libel. From NPR.Misc. (Printed document not on display.) |

It has sometimes been suggested that poetry is too pure

or unworldly an art to engage in politics. Nevertheless, whether writing

scurrilous doggerel, more elaborate satirical essays on human folly, or

works of dignified and elegiac protest, poets have long intervened in

public life. Much of the verse dashed off to land blows in debate is of

negligible literary merit, but the compassion which can underlie strong

political feeling has occasionally given rise to major works. The thousands

of metrical squibs printed in the furtherance of factional party wrangling

show that verse has been seen as an effective weapon by its practitioners,

and in some societies the very act of writing poetry has assumed a political

dimension, as a form of dissent from state control.

Items on display:

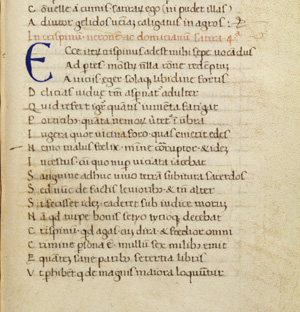

MS Cholmondeley (Houghton) 74/20, 24 and 49:

three poems against Robert Walpole, seized by government agents from the

printing shop of Richard Francklin, examined by censors and docketed ‘Scrutore

3 Sept 1730’. MS Add. 8487/4: Siegfried

Sassoon, ‘Glory of women’, 1917.

|