|

Philosophical Transactions, no. 80

(19th February 1672)

The first contact that Newton had with the wider world of natural philosophers outside Cambridge came at the instigation of Isaac Barrow, who initiated a mathematical correspondence between Newton and John Collins (see catalogue number 38) in summer 1669. In November 1669, Newton visited London and met Collins for the first time. Collins soon learned something of Newton’s latest invention, the reflecting telescope (see catalogue numbers 22–4), and it was probably through him that the Royal Society heard of the discovery at the end of 1671. Barrow again acted as an intermediary, bringing one of Newton’s telescopes to London for the Society to inspect. Seth Ward, Bishop of Salisbury and formerly Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford, immediately proposed Newton as a candidate for fellowship of the Society. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society on 11 January 1672 and, on 18 January, promised the Society’s secretary, Henry Oldenburg (1615–77), that he would send him ‘an accompt of a Philosophicall discovery [which] induced mee to the making of the said Telescope’

(see catalogue 24). This he did on 6 February, submitting the paper

on light and colours that Oldenburg published on behalf of the

Royal Society in his journal, the Philosophical Transactions, on 19 February 1672.

Newton had been involved with the publication of other men’s works from the late 1660s, when he began helping Barrow with an edition of his lectures (see catalogue 32). This was, however, Newton’s own first step into the harsh and competitive world of the communication of scientific discoveries. His experiences on this occasion perhaps helped to generate the suspicion with which he later regarded the printed word. Newton was at first eager to submit his work to the scrutiny of others. He welcomed Oldenburg’s communication of his work to Christiaan Huygens, the pre-eminent natural philosopher of the age, then living in Paris. Yet, as praise for his work began to be tempered by questions about the theories that lay behind it, Newton began to realise some of the dangers of publicity. Correspondence with Oldenburg, and publication in the Philosophical Transactions, drew from Newton some of his most important optical discoveries and speculations, but it also put him increasingly on edge

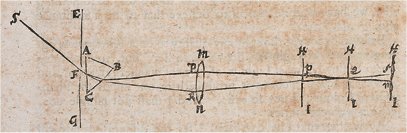

The discoveries that Newton communicated in 1672 were not new to him, but were a summary of some of the main conclusions of his optical studies during the second half of the1660s. In particular, his paper on light and colours contained an account (pp. 3086–7, on display) of his experiments with a prism to show that white light was composed of differently refrangible rays of coloured light, forming a spectrum from purple to red. Yet the confidence and familiarity with which Newton presented his results may have been one of the reasons for the scepticism that greeted many of his findings. Several prominent natural philosophers, in particular Huygens, Robert Hooke, and Ignace Gaston Pardies, soon engaged Newton in a wide-ranging correspondence, mediated through Oldenburg, that questioned both the conclusions and the methods of Newton’s optical experiments.

|