The Anatomy of Generation

The Holy Family pictured on a maiolica childbirth tray, c.1531. These ceramics were ritual gifts to Italian mothers after a birth. Fitzwilliam Museum, MAR.C.60-1912

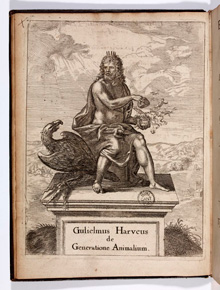

Movable type for printing books was introduced to Europe in the mid-1400s, but a substantial expansion of writing about sex and the body had already taken place. Printing fostered scholarly exchange and patronage, and turned ‘secrets of women’ into market commodities. Male physicians had begun to dissect human cadavers, creating new knowledge about the pregnant female body as well as new authority for themselves. Printed anatomy books used artistic techniques of woodcut and engraving to offer readers spectacular images of the interior of the body. More sensational were cheap broadsheets of monstrous births, but the most common image of generation remained the Holy Family. Philosophers and experimenters debated the ways that character, illness and other qualities might be passed from one generation to the next. As part of these controversies William Harvey argued in a treatise of 1651 that every living thing came from a primordial egg.

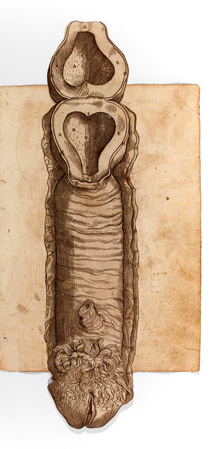

One of the first copperplate engravings in England from Thomas Raynalde’s The Byrth of Mankind (1552), showing a ‘matrix’ (womb), remarkably phallic in form. Peterborough G.4.36

Zeus opening a bisected egg labelled Ex ovo omnia: ‘Everything from the egg’, from William Harvey, De generatione animalium (1651). Adv.c.33.1, frontispiece

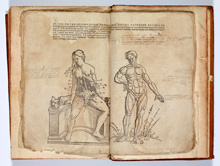

From Omnium humani corporis…(1641),an anatomical booklet made up of woodcut illustrations copied from earlier books under the supervision of Walther Ryff, a prolific producer of texts intended for a broad range of readers. N*.3.17(B)