The Secrets of Women

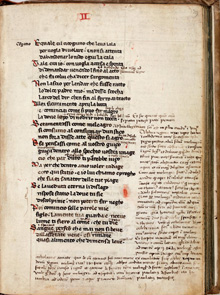

The Roman poet Statius is imagined explaining to Dante how humans come into being and acquire a soul. La Commedia, Purgatorio, canto 25, Italian text accompanied by scholarly glosses and commentary in Latin, in a Venetian manuscript of the fifteenth century. MS Gg.3.6, f. 139

When writing began it was used for charms to encourage conception and prognostics to forecast birth outcomes or determine the sex of babies. In classical debates about generation Aristotle argued that both parents contributed to the making of a new child, but in different ways. Men supplied the form, or plan, while women provided matter, the raw materials. In the Middle Ages these theories were taught in the universities and discussed in vernacular texts for courtly readers, such as Dante’s Purgatorio. Manuscript books called ‘secrets of women’ took advice from learned medicine about sex, conception and pregnancy. They also drew upon recipes that had circulated by word of mouth. Though sometimes addressed to women, gynaecology books were often compiled in monastic communities and employed by physicians. Using the new medium of print in his romance Pantagruel, the French doctor François Rabelais satirized these learned tomes.

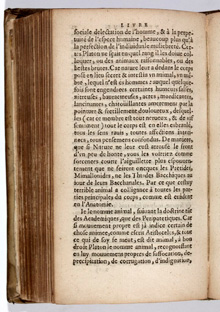

François Rabelais, a university-trained physician, satirizes learned theories of generation in Les Oeuvres de Me…(1558). Keynes E.3.17, p. 134

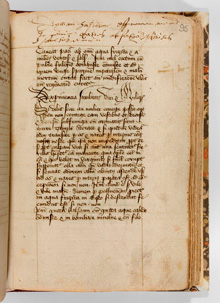

In the fifteenth-century manuscript Experimenta sterilitatis viri et mulieris fertility tests were written in Latin into the book whose main text consisted of medical remedies in English. MS Ee.1.13, f. 95r

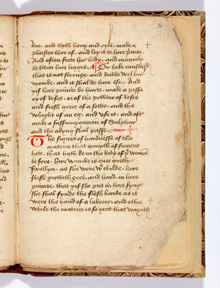

This rare, English fifteenth-century manuscript The Knowing of Woman’s Kind in Childing is intended to be read by women so that they do not have to talk about their gynaecological problems with male practitioners. MS Ii.6.33, part 2, f. 31r

.jpg)

Limestone statuette of Isis and Horus from Egypt, Ptolemaic Period, around 300–200 BC. Fitzwilliam Museum, E.59.1937