The Tyrant-Hater

On 30 January 1649 the English decapitated their monarch, and in March Milton was appointed Secretary for Foreign Tongues to the republican government. He knew that overwork might blind him, but wrote that fate had made him choose ‘either to lose my sight or to desert a high duty’. Among other tasks Milton was required to defend the Commonwealth against Royalist propaganda. The combination of lofty principle and vituperative partisanship in his defences was characteristic of the period, but even by the standards of the time the vicious ad hominem exchanges in which Milton engaged were remarkable; later in the seventeenth century he was censured for his ‘billingsgate’ (fish-market) language, and in the nineteenth the historian Lord Acton dismissed these writings as ‘ribaldry’. Milton’s unbroken strain of opposition to tyranny nevertheless won him enduring honour in the annals of English radicalism, and in 2007 he was still cited by a British Prime Minister as a way-mark in the development of this country’s freedoms.

|

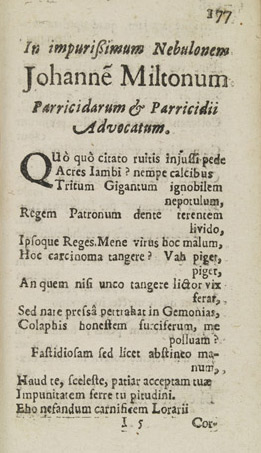

‘In impurissimum…’, from Du Moulin’s Regii

sanguinis clamor (The Hague, 1652). D*.13.14(G) |

|

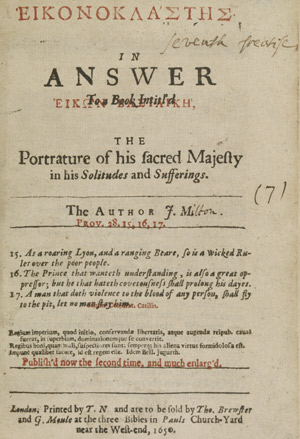

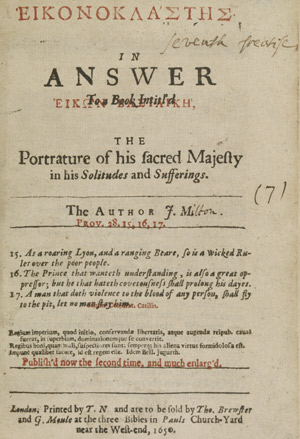

Έικονοκλάστης [Eikonoklastes] ( London, 1650). Bb*.9.47(E) 7 |

|

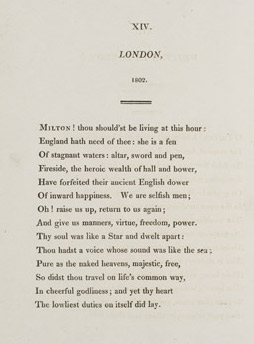

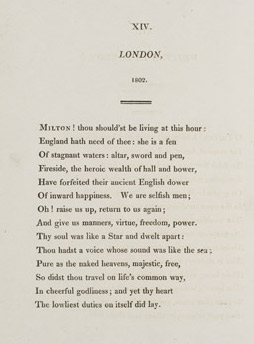

Wordsworth’s celebrated invocation to Milton. Robert Graves retorted that those who quote the sonnet with approval ‘should read, or re-read, Milton’s life and works’. S721.c.81.11 |

|